Welcome to the Uncle Tom Housing Development

The “Forest Settlement” (Waldsiedlung Zehlendorf), as the development is officially called, or the “Uncle Tom Housing,” as the settlement was quickly nicknamed and still popularly called, was designed by the architect Bruno Taut and built by the non-profit housing association GEHAG, the Gemeinnützige Heimstätten-, Spar- und Bau-Aktiengesellschaft (Public Benefit Homestead, Savings, and Building Cooperation), in the construction period of 1926—1931/32.

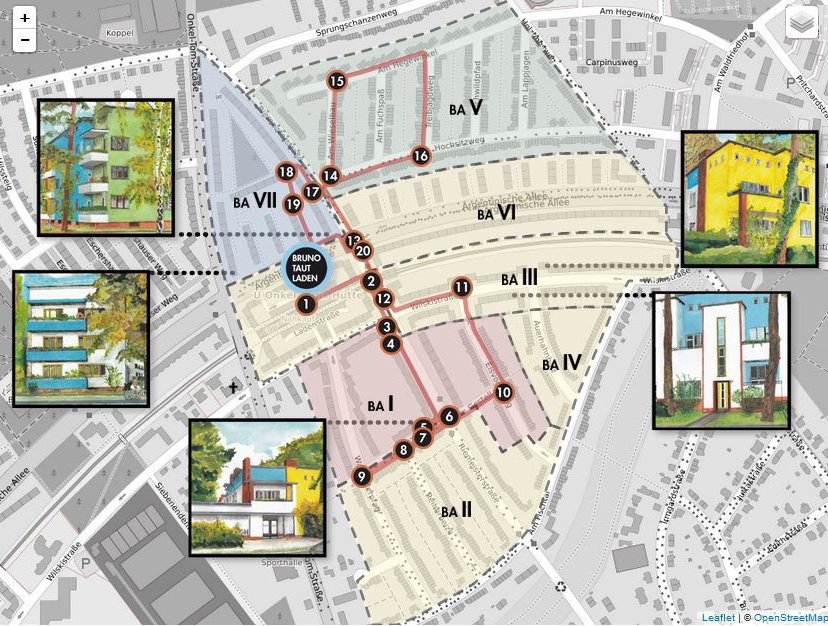

We appreciate your interest in the development. This interactive tour will guide you through the various areas of the settlement and provide you with historical and architectural details, as well as interesting anecdotes.

If you would also like to visit the private “Pine Courtyard” (Kiefernhof), we will gladly lend you the key to the gate at the starting point of the tour in the Bruno Taut Shop.

This guide will take you on a tour of the settlement of which 21 locations are described within a timeframe of about two hours.

Start of the Uncle Tom Story Map Tour

The Origin Of the Settlement

The socio-political situation after the First World War was characterized by catastrophic housing shortages. Millions of apartments were needed throughout the German Empire (Reich) and hundreds of thousands in Berlin. Many families were housed in inadequate, unhealthy living conditions in severe overcrowding under oppressive conditions. The term “Stone Berlin” characterizes the lack of open space and green areas within residential properties as well as the surrounding environment.

The construction of apartments in the Empire was determined exclusively by the private sector. The state only subsidized the housing supply of civil servants, the military, the railway, the post office and the like. This was mostly done by cooperatives in the role of developer. Religious institutions and charitable foundations of individuals and humanitarian aid supplemented this system. However, this only had a quantitatively minor effect, since industrialization and urbanization had greatly increased demand since the last third of the 19th century. It was only in the course of the First World War that a housing movement for returning—often invalid—soldiers led to direct financial state aid at the “last minute”.

Towards the end of the First World War, the population of Berlin practically doubled to over 4 million. The spike is also the result of the Greater Berlin Act (Groß-Berlin-Gesetz) of 1920, which incorporated surrounding towns of Brandenburg into the city of Berlin and created 20 boroughs, many of which we are familiar with today, such as this one—Zehlendorf, and increased the city’s area from 66 km² to 883km². Just during the Twenties 400,000 new Berliners arrived. Thus, a housing shortage took on dramatic proportions. Housing became a political priority.

With the German Revolution (Novemberrevolution) of 1918 came a democratic parliamentary republic, the abdication of Emperor Wilhelm II and the abolition of the Prussian three-class voting system based on income, property and trade taxes paid. The wealthy bourgeois belonged to the upper tax class since they paid the most tax, and as a result, dominated the parliament with more representation than the lower tax classes. These “homeowners’ parliaments” (“Hausbesitzerparlamenten”) could determine property ownership which had led to property speculation. For the first time ever, the Weimar Republic, with its initial social-democratic majorities, took responsibility for the housing problem as a state. Corresponding regulations were included in the Weimar Constitution in 1919, such as Article 153, “Possession creates responsibility: use of the land must serve the common good.”

Only after the hyperinflation of 1921-1923 and the stabilization of the Reichsmark in 1924 was it possible to create the financial basis for implementation of new housing. This was achieved with the U.S. financial resources of the Dawes Plan, increased commitment of the municipalities, and in particular with the so-called Hauszinssteuer (house rent tax) in 1924. Mortgages had lost their value due to inflation but the land had not. Borrowers retained their property essentially without having to pay the remaining principal or interest since they were payable in almost a valueless currency. The federal government levied a tax on these buildings built before the First World War, taking advantage of the situation as a source of revenue. These tax funds were partly used to subsidize public housing. From 1924 this triggered a wave of establishing housing associations on municipal and state bases in which the trade unions played an active role.

The Berlin-based non-profit GEHAG housing association, founded in 1924, as well as the empire-wide GAGFAH (Gemeinnützige Aktiengesellschaft für Angestellten-Heimstätten), the Public Benefit Corporation for Salaried Employees’ Homesteads, founded in 1919, belonged to these newly established housing associations. GEHAG was a subsidiary of DEWOG (Deutsche Wohnungsfürsorge-Aktiengesellschaft), the German Housing Association of the Free Trade Unions, and carried out the task of building apartments for civil servants, employees and workers throughout the Republic. Dr. Martin Wagner served as chairman of the board of the Berliner Bauhütte (construction guild) and was a leading figure in the national movement to socialize the building trades (guild socialism).

Initially the GEHAG created some smaller housing developments, but larger developments followed. The so-called “Horseshoe Estate” (Hufeisenseidlung) in Britz was the first large housing estate (1925-33) and the local “Forest Settlement” (Waldsiedlung Zehlendorf) followed, starting in 1926, and every effort was made to retain the wooded character. GEHAG had appointed Martin Wagner as manager to plan and supervise the project. In the same year he became a director of the Berlin Municipal Council responsible for building and urban development as Ernst Reuter did for the Department of Transportation.

The three architects Bruno Taut, Hugo Häring and Otto Rudolf Salvisberg designed sections of housing according to Taut’s urban planning design, which evolved with each phase. The construction of the settlement took place for about 5,000 inhabitants in about 2,000 residential units, of which 1,100 were rental apartments and about 900 single-family-owned row houses.

The land of the entire settlement area was acquired by Adolf Sommerfeld, the owner of the Zehlendorf Building Corporation (Zehlendorfer Terraingesellschaft, AHAG). Martin Wagner had skillfully secured city financial support and official approval before the project had become public knowledge. The politicians represented the bourgeois Zehlendorf and were only interested in creating new housing in keeping with their villa community as individual, free-standing houses with pitched roofs on a mostly picturesque small scale for the upper tax bracket.

The beneficiaries of the new constitutional article, however, were not their sought-after wealthy clientele, but the lower income groups. „The distribution and usage of real estate is supervised by the state in order to prevent abuse and in order to strive to secure healthy housing for all German families, especially those with several children, with a living and working environment appropriate to their needs“ (Weimar Constitution, Article 155).

“GEHAG’s success in obtaining this particular site to provide housing for low-income workers was a triumph in breaking through social barriers. As could be expected, it caused howls of protest from those interested in retaining their privileged status” (Wiedenhoeft, Ronald; Berlin’s Housing Revolution: German Reform in the 1920s, UMI Research, Ann Arbor Michigan, 1985, p. 109).

After the Greater Berlin Act of 1920, the clashes between the district and the GEHAG even included the Berlin Magistrate under Mayor Gustav Böß and the Prussian ministerial bureaucracy. For example, the city had to override an arrest warrant issued by the district against the building supervisor Martin Wagner and the architect Bruno Taut for unauthorized start of construction.

In the first years, the apartments were assigned by the district housing office on the basis of a strict list of criteria, not by the housing association GEHAG itself.

Martin Wagner, Bruno Taut and many other committed trade unionists, politicians, architects and like-minded people at the time worked and fought for affordable lower income housing in a better living environment to promote improved health and social and cultural well-being.

In 1990, the regulations for the non-profit housing industry were finally repealed. In the year 2000, the GEHAG was sold (i.e. privatized) by the Berlin Senate with the approval of the House of Representatives. Seven new owners followed in succession, including U.S. hedge funds. At the end of this chain today is the „Deutsche Wohnen“, a merger of the U.S. company Oaktree Capital Management and a subsidiary of the Deutsche Bank, now a listed company with one of the largest housing stocks in Germany.

Thus the socially-committed company GEHAG, the public benefit housing association, with a profit orientation limited to 4 percent, became a listed stock-exchange company. As a result, many tenants left “their” settlement due to painful rent increases from various modernization costs. Meanwhile, vacancies are for the most part non-existent. A new generation is currently moving into the terraced houses that do become available and filling the kindergartens.

One must be grateful that the forest settlement Uncle Tom’s Cabin has been listed as a historic monument since 1982, which prevents worse alterations. This was achieved through the initiative of architects living in the settlement, who objected to ongoing changes and renovations not in keeping with the original design.

The „Deutsche Wohnen“ supported the reconstruction of the houses along Wilskistraße up to Waldhüterpfad according to historic preservation requirements in recent years.

May this guide help preserve the consciousness of the complex factors which contributed to the uniqueness of this housing development and to give new inhabitants appreciation of their home.